Healing Broken Connections: Restorative Justice in Scotland's Northeast

In Peterhead, Scotland, the local Methodist Church and Action for Children join their forces to help restore family ties challenged or broken by imprisonment.

11 December 2024

11 December 2024

"The difference between criminal justice and restorative justice can be shown in three questions," explains Deacon Douw Grobler, a former Prison Fellowship executive director from South Africa. "Criminal justice asks what law was broken, who's guilty and what punishment they deserve. Restorative justice asks who was hurt, what they need to be healed, and whose obligation it is to help."

This perspective drives a transformative mission in the northeast of Scotland, where Douw and the Methodist Church in Scotland are pioneering a radical approach to supporting families affected by imprisonment. Working primarily with HMP Grampian in Peterhead, their programme addresses a sobering reality: approximately 27% of inmates re-offend within 24 months of release.

Families of offenders are often invisible victims, bearing the weight of shame, marginalisation and economic strain. By providing support meetings in the form of conversation cafes, organising family picnics and facilitating prison visits, they aim to rebuild fractured community connections.

Douw’s background in international restorative justice training—having worked in Zimbabwe, Namibia, Swaziland, and South Africa—provides a unique perspective. He understands that true rehabilitation requires more than punishment; it demands healing and reintegration – the restoration of relationships between the offender, the family, and the community.

The challenges are significant. Limited funding, declining church resources and vast geographical distances complicate their work. Yet, the Methodist churches remain committed to their mission of community service, viewing these initiatives not as membership drives, but as embodying Christ's call to reach out.

"The greatest harm you can do to these broken families is to break promises," Douw emphasises, highlighting the critical need for consistent, long-term support that can genuinely transform lives.

“Last week, a young woman, with a child who was less than a year old, drove up from Liverpool. She told us that she was driving for four hours, stopping, seeing to the baby and having a cup of coffee, before driving again. And that takes a lot of planning and a lot of effort,” explains Edith from Action for Children.

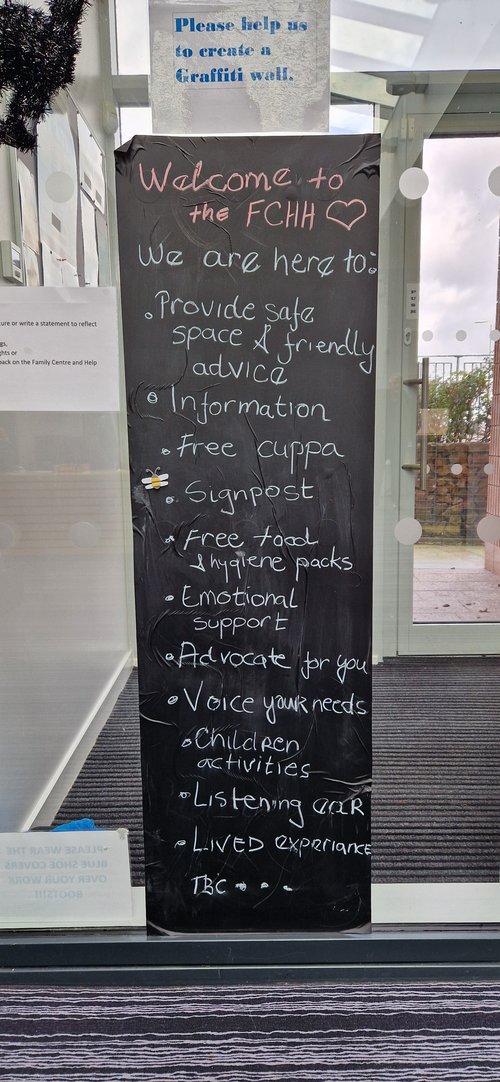

At HMP Grampian’s Family Centre, Edith is crafting a delicate support network for families navigating the complex emotional landscape of imprisonment. Her work reveals the profound challenges faced by families whose lives are touched by incarceration.

"Where's the superhero for a child affected by imprisonment?" Edith asks pointedly. "There isn't one." Her words highlight the stark reality for children who are often overlooked and stigmatised, through no fault of their own.

The centre supports approximately 27 families per month, representing 52 children, with nearly 30% having special needs or neurodivergent requirements. Edith and her team create spaces of normalisation and healing, organising conversation cafés, family picnics and even a Christmas party where prisoners can collect gifts for their children.

"Eating together is important for families," Edith explains, describing their carefully planned Christmas events where each family gets a private table to share a moment of connection. These seemingly simple gatherings are profound acts of compassion, helping to rebuild dignity and hope.

The challenges are immense. Families travel hundreds of miles, often at significant personal expense, to maintain connections with incarcerated loved ones. Many face social stigma, with children experiencing cruel treatment from peers and communities.

By providing a safe, nonjudgmental space, Edith and her team help families navigate the complex emotional terrain of imprisonment, offering support far beyond bureaucratic, light-touch assistance. "We have to adapt to what families want and what they think they need," Edith says, embodying a philosophy of genuine, person-centred care that sees beyond statistics to the human beings behind them.