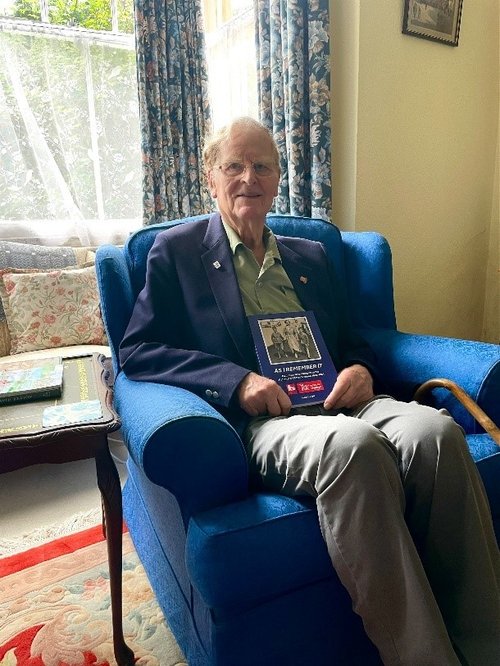

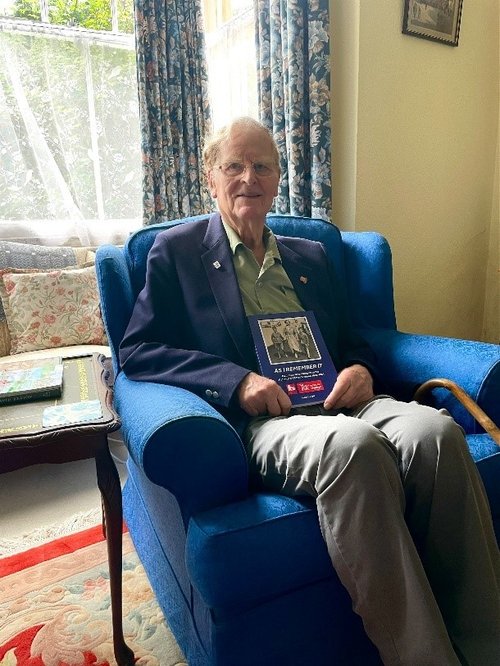

Why did Revd John Travell decide to write his childhood memories at age 94? Born in a workhouse, he grew up from the age of four at the National Children’s Home (now Action for Children). In As I Remember It, John shares his experience to raise awareness of the worrying situation in childcare – a mutual concern with Action for Children which has been campaigning relentlessly to help children and give them a happy and safe childhood.

This vivid and critical work comes from a writer with a remarkable memory who thoroughly researched public records and delved deeply into the subject. John acknowledges the invaluable start the National Children’s Home provided while also offering constructive criticism. He particularly praises the post-war changes that transformed large institutional homes into small, mixed-age and mixed-sex family units led by dedicated individuals who treated their charges as their own. These changes brought individual care, love and joy into the children’s lives.

What inspired you to write your autobiography?

I didn’t intend to and resisted the idea for a long time. I’m naturally reserved and have never found it easy to talk about myself. Indeed, one of the voices inside me told me to keep quiet about having grown up in a children’s home and to share my personal history only with my friends and family. But then four things happened:

- About a year ago I obtained my very detailed file from the National Children’s Home, which told me a lot I didn’t know – including the fact I was born in the workhouse.

- Then my family – especially my daughter Diana – wanted to know more about my upbringing.

- Some friends of mine seemed very keen that I should tell the story of how – from a workhouse and children’s homes – I became the man they know today.

- Finally, Alice Thomson in The Times wrote an article revealing the very worrying situation in child care today – such a contrast with my own childhood experience and something that needs urgent reform.

How did you decide which events and experiences to include?

I thought chronologically – from the beginning. I’ve still got a good visual memory which enabled me to picture many of the events in the book. For example, I can still remember as a tiny boy sitting on the huge staircase at Barton-on-Humber being taught to tie my shoelaces. The memories came and I found the story – quite a short one – flowed. I wrote the book quickly and it was in print in a matter of six months but, of course, many of these memories had been fermenting for eight decades or more.

Were there any parts of your life that were particularly difficult to write about? Did you discover any new perspectives on your past while writing?

My original draft was more cautious and guarded. It described what happened and who I met, but a friend of mine who also writes books encouraged me to include how it seemed to me and how I felt. My National Children’s Home reports repeatedly said I was slow. They often made judgments of us based on observation but seldom listened to our views. I was often anxious and could get very flustered. Aged ten, I met the Governor of the Harpenden Home for the first time: I couldn’t speak and he got cross with me. Later I found I enjoyed acting but still got very shaky when asked to read the lesson in church as myself. Writing some of these private memories was a challenge.

Writing about my mother made me think a lot about her. I also talked to my daughter Diana and discovered stories my mother had told her years later which I didn’t know. My mother never lost touch with my brother and me. Wherever we were, she never let go. My National Children Home file contains all her letters, enquiring about us, arranging to come and see us and keeping a parental eye on our wellbeing and progress. I find that very touching and it was important because we all need someone to whom we are special – someone we belong to. She was remarkable and I realise that more now than I did before I wrote this book.

It also gave me a better perspective on the developments of childcare that took place during my childhood. My days at the NCH were rather like being a boarder in a public school. We did as we were told. We were all boys of similar ages and we had a good relationship with the mostly excellent staff who looked after us. But no one loved us. And that’s important to any child. The changes that Audrey Wilson and John Litten introduced broke these big houses up into small, mixed family groups each with a sister – like my friends Florrie and Lilie – who saw them as their family. This introduced not only family relationships and love but also enabled each child to be related to as an individual depending on his/her needs.

How did you feel once the biography was completed and published?

Very pleased to have done it. It’s obviously a very personal story to me but I hope it will ring bells with others and show just how much was done in the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s to look after children like me. I owe many people a big debt and this book explains why.

It’s also made me expose my personal story – which I’ve always been a bit reserved about. I’m still getting used to the idea of having shared it widely.

What do you hope readers will take away from your story?

I hope it will be used in the debate that’s going on now about childcare. I feel strongly about this. In 1957 Audrey Wilson reported on progress so far and expected that progress to continue. Instead, it has deteriorated. I’m sure children of my generation got better care than many do under the present arrangements. And that worries me very much indeed. Our care for the vulnerable should get better, not worse. Today’s arrangements, allowing some private equity companies make fat profits out of childcare, seem to me scandalous. Under the arrangements established by the Attlee Government, this would have been illegal. It should be now. And I want people to know about it. I hope my book helps them understand what we have lost and why we must do our absolute best for children today.