All Saints - is Halloween a "thin place"?

Is there a case for reclaiming Halloween as an intrinsic element of the Christian celebration of All Saints? Laurence Wareing believes there may be.

The Scottish Church leader and founder of the Iona Community, George MacLeod, used to describe the island of Iona as a "thin place" – where barely a sheet of tissue paper “as thin as gossamer” separated the material from the spiritual. It was an image borrowed from the broader Celtic idea that there are places where God is experienced more nearly than others.

In another Celtic tradition, it was once believed that at the festival of Samhain (pronounced “sow-in”), the boundary between the worlds of the living and dead became blurred. Celebrated on the last day of October, the festival marked the end of summer and the harvest season and the beginning of the dark, cold winter during which death was a common occurrence.

In choosing this day to recognise the presence of otherworldly spirits, whatever their malevolent intentions might be, were the Celts also acknowledging that there is no hard and fast division between our day-to-day material world and the spiritual world? The world beyond death lies closer to us than we often permit ourselves to remember. Was not the festival of Samhain a celebration of the “thin place” in which we live; an acceptance of the tissue-thin division between the living and the dead?

Via the Romans, who combined Samhain with their existing celebrations of Feralia (commemorating the passing of the dead) and the honouring of Pomona, the goddess of fruit and trees, Samhain was eventually morphed into All Souls’ Day (2 November) – a Christian attempt to replace the Celtic festival of the dead with a related, but Church-sanctioned holiday. But Samhain has lived on its own right as All-hallows Eve – the night before All-hallowmas, known more usually as All Saints.

(Image: Skulls painted for the Mexican Day of the Dead festival)

Today, many Christians feel ambivalent at best about marking a festival that allows free rein to evil spirits before they are sent packing by the holy forces of the saints. We are happy enough to sing about the continuing presence of angels (“Still through the cloven skies they come, / with peaceful wings unfurled” StF 205) but the less understandable, less controllable manifestations of death and evil are increasingly taboo.

Is it because we have forgotten that the two festivals are conjoined – that Halloween makes more sense when reunited with its equal opposite, All Saints? Does the rejection of Halloween by many Christians (unlike other, apparently more acceptable, Christianised “pagan festivals”) say something about our desire to shut out our contemplation of death? If so, then it’s an attitude challenged by the lectionary Gospel reading for All Saints Day, which records Jesus’ raising of Lazarus out of death. (John 11:32-44).

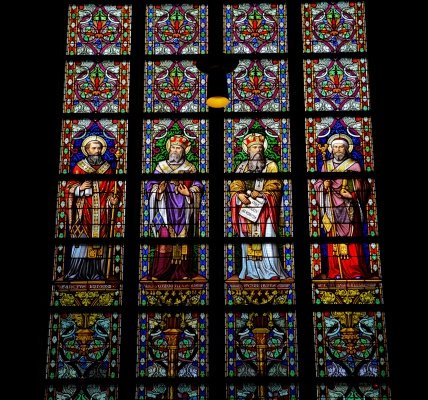

How may we reclaim our saints from stained glass windows?

The raising of Lazarus is an event that signifies the dramatic presence of God even – and perhaps especially – when other powers appear to be at the fore. It’s a story that enacts the words of the prophet Isaiah: “On this mountain, he has destroyed / the veil which used to veil all people, / the pall enveloping all nations; / he has destroyed death for ever.” (Isaiah 25:7-8a)

We have compiled some suggestions of hymns that reflect both Halloween and All Saints Day. Why? Because, taken together, the festivals of All-hallows Eve and All Saints remind us that we are connected to our past, and that those who have gone before us still live with us and may help support us into our future. Using vivid and unsettling imagery, the twin festivals insist on the wholeness of creation – God is God of the dead as well as of the living. If we remain alert to the non-material aspects of our lives, we may remember that the division between our lives and theirs is tissue thin.